Jayse Hansen explains the screen UI design behind the action-packed sequel.

By Meleah Maynard

Renowned Futuristic User Interface (FUI) Designer Jayse Hansen is known for his work on a long list of blockbusters, including “Star Wars,” “The Hunger Games,” “Iron Man,” “Batman,” “Spider-Man,” “Guardians of the Galaxy” and many more.

We talked with him recently about the screen UI designs he created for “Top Gun: Maverick,” a sequel to the 1986 “Top Gun” film starring Tom Cruise as Pete “Maverick” Mitchell.

Working in collaboration with Lockheed Martin, Hansen used Cinema 4D, After Effects and Illustrator to design and animate the film’s storytelling hero screens. Here’s what he had to say about his creative process.

How did this project come to you, Jayse.

Hansen: My legendary buddy Bradley “Gmunk” Munkowitz was directing a team of badass lead designers Nicolas Lopardo and Toros Köse. Lopardo called me up as they were looking for some wingmen to handle the day-to-day on-set graphics during filming.

Our newly formed crack squad was led by the famous VFX Supervisor/Animator David “Dlew” Lewandowski, and included me on design and animation and James Heredia rockin’ the keyframes.

At first, it seemed like we’d only be attached for a few weeks, but it turned into about four months of design and animation as they wrote and evolved the story. These iterations are always, rush, rush, rush because they’re filming, and you’ve got to have things ready for them when they need them.

Tell us about your process.

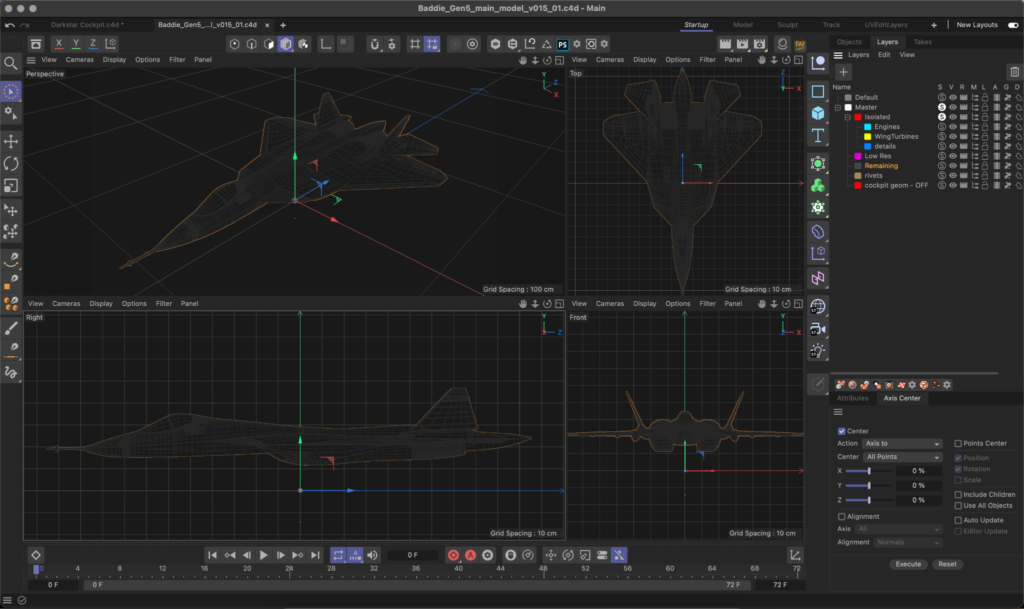

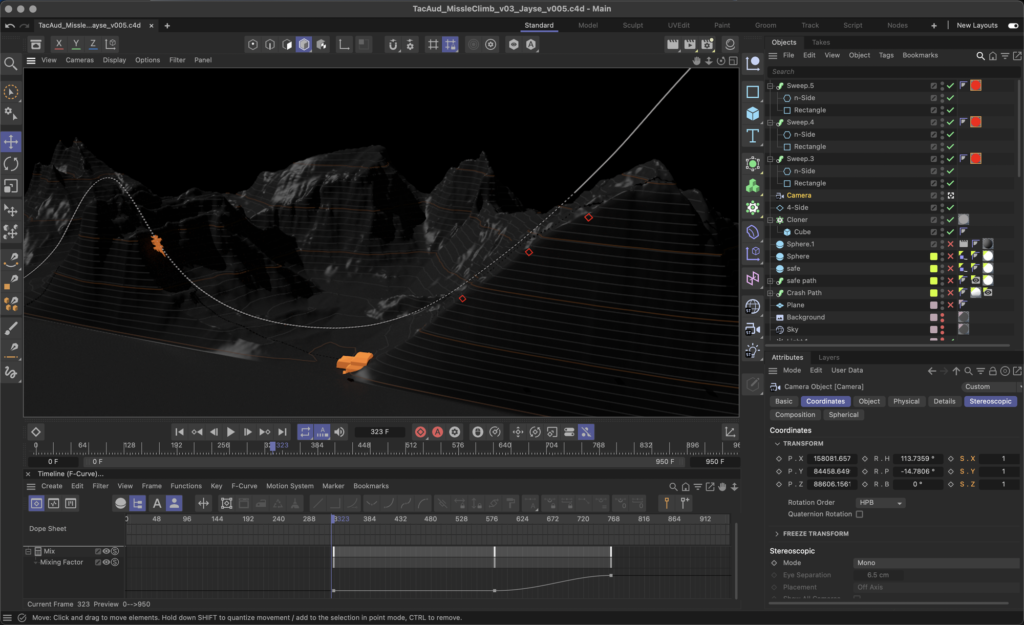

Hansen: Cinema 4D always plays a major role in all of the screens I do for films, and that’s even true of scenes where you might think something is 2D. I start by sketching on paper, and then I go to Illustrator and then into C4D and After Effects. I go back and forth, and the final renders come out of After Effects, either as Quicktimes for the playback screens on set, or EXR sequences for the final film.

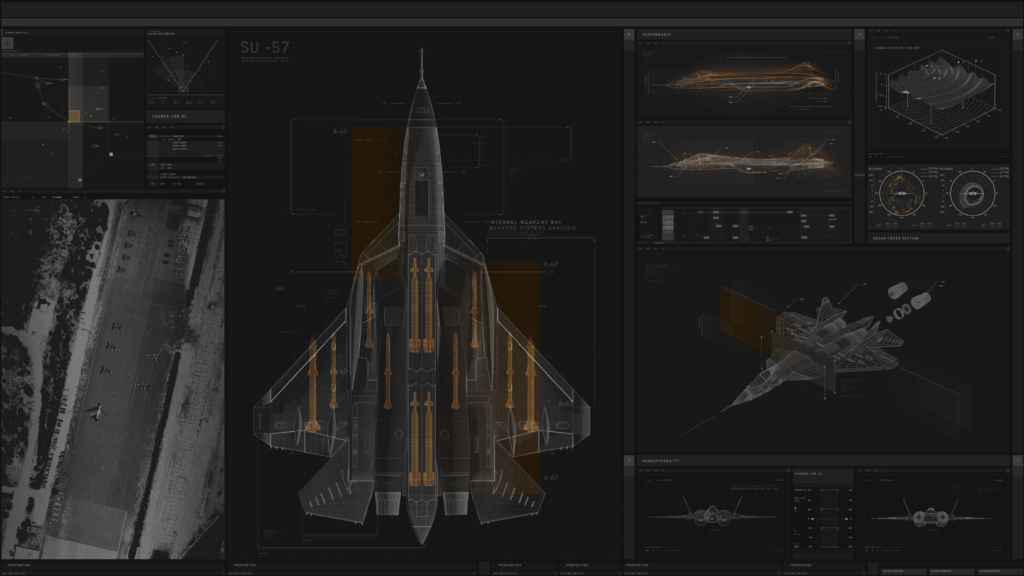

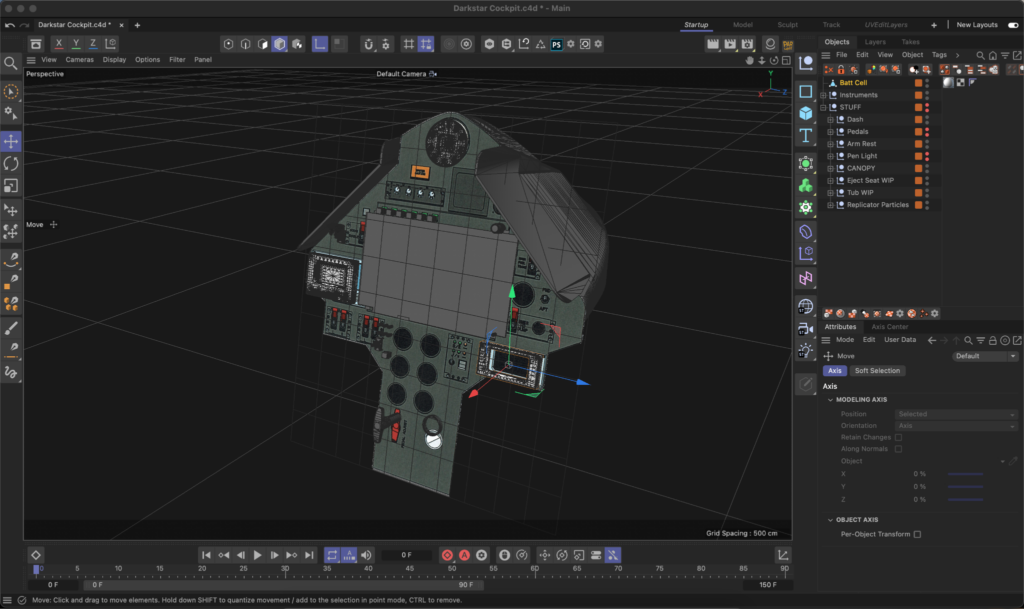

I used C4D for the Darkstar cockpit and mission control, as well as for the F-18 “Who’s in the air?” schematics, the 5th-gen bad-guy fighter jet schematics and working out the 3D aspects of the training scenes.

Your attention to detail is extraordinary. How did that come into play for this film?

Hansen: Well, I’ve spent the last four or five years reimagining future fighter jet cockpits for films and real-world, next-gen designs. So, by the time “Top Gun: Maverick” came along I was like, ‘Oh, this is totally my jam! Let’s go!’

I’m just so curious about how all these systems work and are displayed to an audience. Some artists just aim to make things look cool, or super complicated, without understanding the function. But to me, that is a huge missed opportunity. And those kinds of designs often tend to look and feel kind of like clip art.

I’ve always loved the artists that really get into their jobs, like a costume designer who knows exactly how tiny fabric patterns will reflect light or fit a certain period in time. I do a similar kind of research for screens. It’s work, but it’s really just part of the fun.

How did you do research for this?

Hansen: I’ve created huge databases of military and aerospace UI references and guides. I often have to find my own experts to consult with for films, but with “Top Gun: Maverick,” they assigned them to me.

There were so many meetings with pilots, as well as experts from Lockheed Skunk Works, a tight-knit, super top-secret division at Lockheed Martin that makes the latest-and-greatest stealth planes.

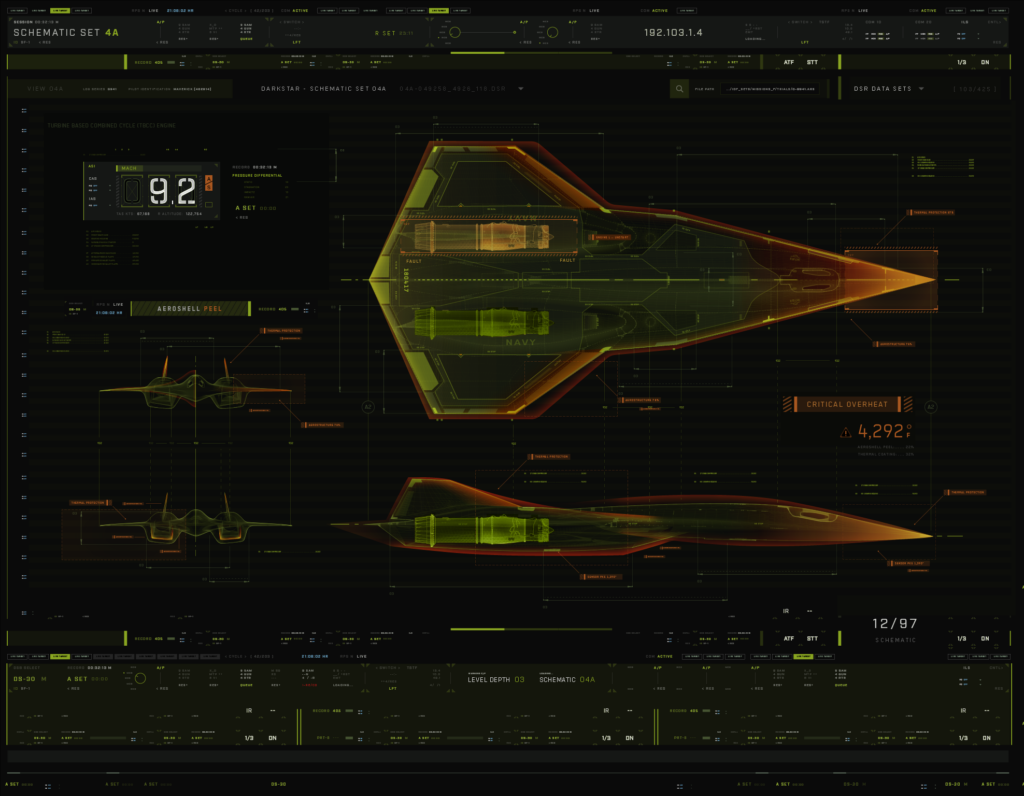

It was great because I could call them anytime, nights, weekends. I was basically a kid in a candy store. They were very involved in the opening scenes with the cockpit and mission control screens for Darkstar, Maverick’s next-gen, hypersonic fighter jet.

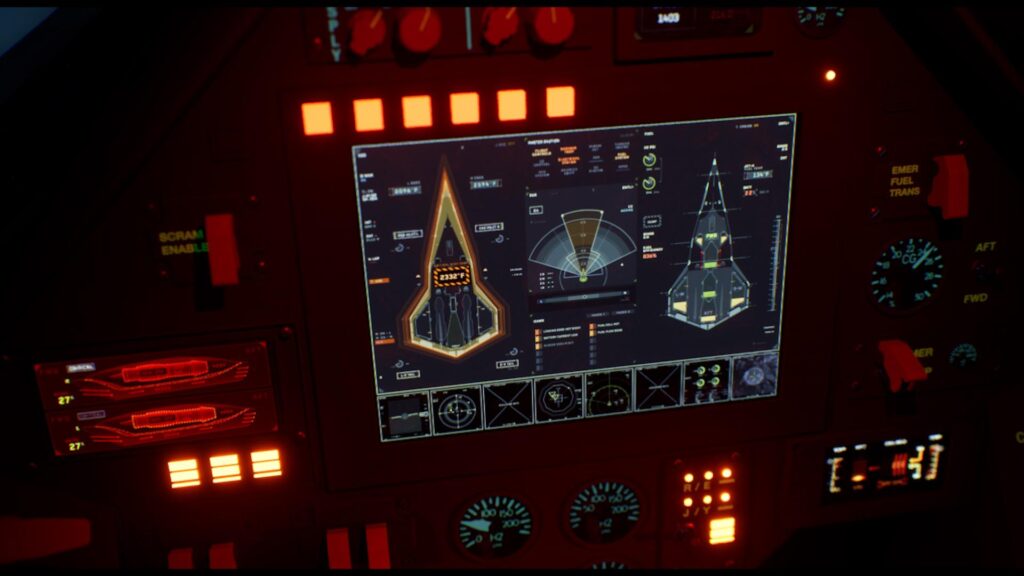

It was important to Lockheed and Tom Cruise that the cockpit’s displays depict the full flight in real time as it would happen in real life. That was so Tom could react to the controls and situations as they filmed, and it was the big “wow” opener that set the tone for Maverick’s character. If they got it wrong, they’d lose the audience from the start. So there was both a lot of pressure and excitement in the prep.

Tom’s a great pilot and took a lot of pride and ownership over organizing the Darkstar cockpit to his liking. I would work with his notes on specific placements of the displays and what could make it all more cinematic.

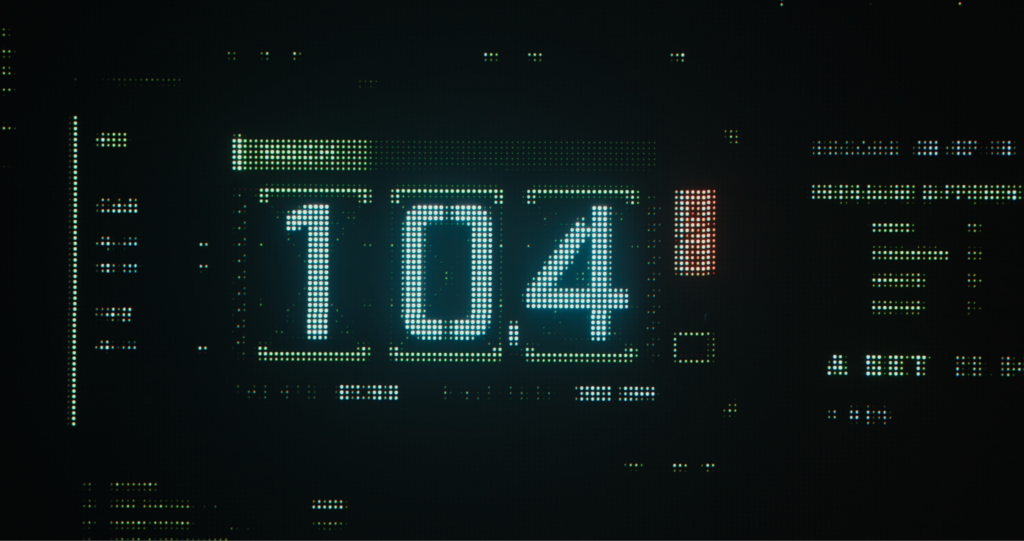

We also did all of the massive screens for the Darkstar Mission Control center. For any designs that we’re doing, I always try to get the important parts to read in a second. I don’t know how long things will be on screen, or how zoomed in or out they will be. So I always try to make important parts read “at a glance, like the mach number display.” (Shown in the upper left corner of the image below.)

I designed it to be detailed, but the important part, the number, is easily readable. That turned out to be a good thing because we suddenly learned that the twenty-foot, high-resolution Sony display had to be swapped at the last moment with an extremely low-resolution billboard display. I think it had fewer vertical pixels than an old Nokia cell phone!

As a designer who moves pixel-by-pixel, that was a nightmare. I couldn’t sleep. But, as a testament to the skill of director Joseph Kosinski, he worked with it like a pro and got insanely tight shots. In the final cut, he used them repeatedly to add intensity to whether Maverick would reach mach 10. In the end, I love the extreme pixelation, as it really adds to the art and drama of the final scenes. It just feels real in a way that a perfectly clear graphic wouldn’t have.

What was it like working with Skunk Works?

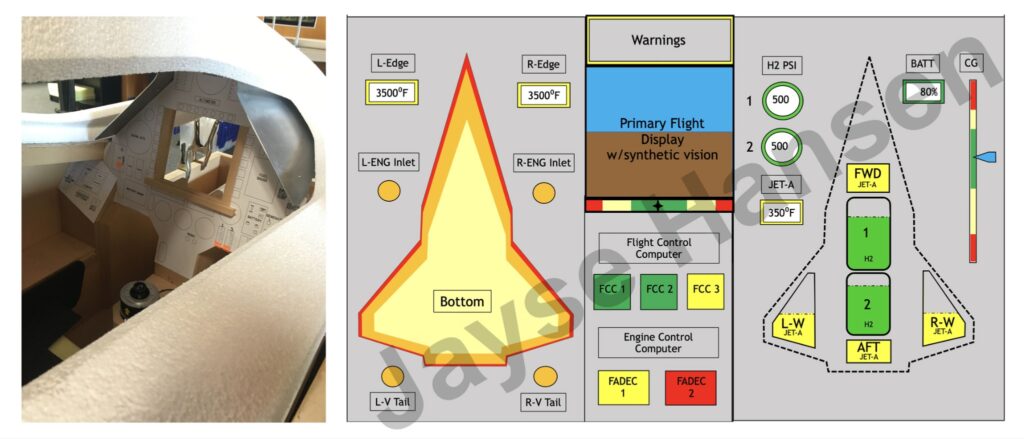

Hansen: When I needed to do the second-by-second real-time animation of the Darkstar cockpit breaking up, I got to work with Skunk Works’ subject matter expert Norman “Spock” Eliasen. I would ask him a barrage of questions, and he would give me back PowerPoint presentations and PDFs from the team that I could design from.

As the cockpit was continually being physically reworked by Tom and crew, I built mockups of it in Cinema 4D to help get a spatial sense for where the five displays I designed for would be located.

These kinds of details were really important to Tom. As a pilot himself, he knew other pilots would freeze-frame the screens, and he was right. Almost immediately there were dozens of YouTube videos and articles breaking down the sequences frame by frame from pilots’ perspectives, analyzing the HUDs and displays.

Say more about the use of 3D for the film’s UI?

Hansen: It’s interesting because this film is the first time anyone has asked for everything to be done in 2D. I think the director really wanted a more low-fi look compared to his other films, like “Tron” and “Oblivion.” Definitely no holograms!

But we were able to use 3D in some F-18 sequences, and we made it look almost 2D. I worked with Dlew on all the modeling, animating and initial rigging for the 3D training sequences. As the story kept tightening in post, Blind also rocked some of the finals on those.

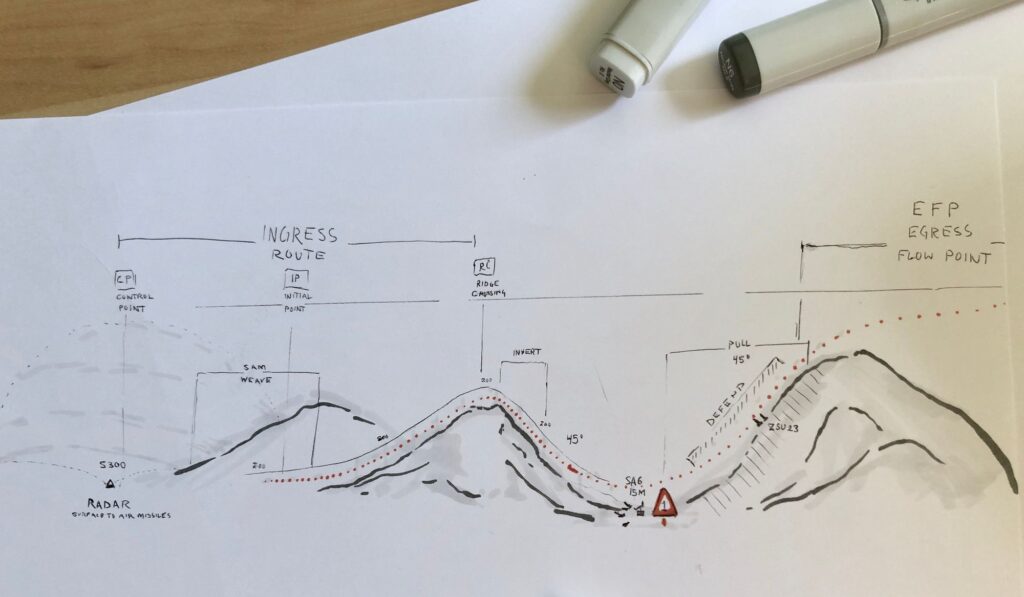

Working from different drafts of the script, I consulted with my F-18 fighter jet pilot Dave “Schleprock” Biggs. I’d draw out the sequences in 2D and 3D, and we’d use those in meetings with Kosinski. Then, Dlew and I would craft them in Cinema 4D and render them for the big training screens.

Was any one part of this particularly challenging?

Hansen: I’d say this film had a lot more weekly script revisions than usual. But it was understandable. As they worked out with the Navy what they could and couldn’t do with the real F-18 jets, they would rewrite, and I would redesign.

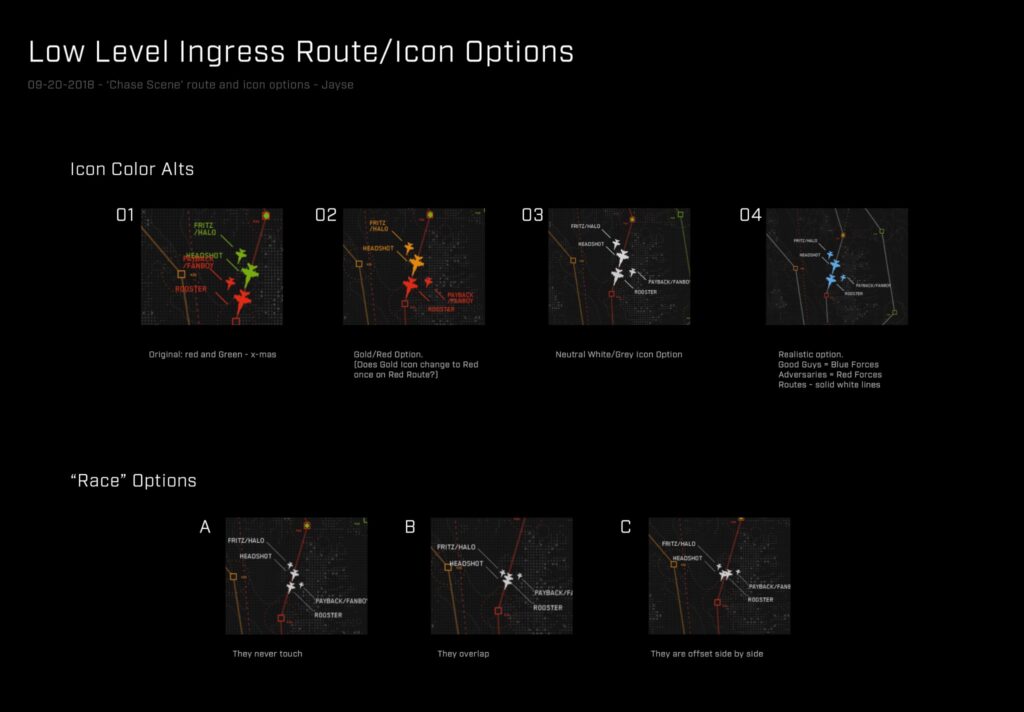

In the original script, the pilots are being shown how they’re going to have to fly really low to avoid being detected by the radar of the enemy’s air defense systems. There were three routes they wanted shown in green, red and gold. When I designed those, it looked really cool on the map, but it wasn’t easy for the audience to follow. The scenes were rewritten over and over again, and they finally decided it should be just one route so the audience would not be overwhelmed or lost.

How else are you using C4D in UI design these days?

Hansen: I’m using C4D more and more in UI design. With VR and AR and Apple’s new glasses coming out this year, spatial user interfaces will be all around us soon. Those interfaces exist like holograms, all around you, rather than trapped on your screen.

In the very near future, we will wrap the UI around furniture and other physical objects, so it complements and integrates with those things, more like great interior or product design. Imagine that your fridge, stove or coffee pot could have a UI that’s part of the physical design of it, rather than just having a flat little screen stuck on like we currently suffer from.

I’m loving that exploration because humans are meant to work in three dimensions. User interfaces can feel really natural and disappear out of the way when we don’t need them if they’re designed to work with our environment.

One of the spatial UIs I’m developing at Army Research Labs allows commanders in a next-gen tank to put on a Varjo XR-3 headset and see completely through the interior. As you can imagine, having this view while completely protected is vitally important. I’m making sure they also have sweet holographic 3D maps at their fingertips.

What are you working on these days?

Hansen:

I’m working with Disney Imagineers to create UIs, holograms and visuals for Marvel-themed attractions. And I’m working again with some of the Navy people from Top Gun. I can’t say much about it other than it involves some pretty insane holograms and, of course, future fighter jet displays.

Meleah Maynard is a writer and editor in Minneapolis, Minnesota.