Amrit Pal Singh’s NFT-Ready Toy Face Portraits and 3D Rooms Are the Future of 3D Art.

By Bryant Frazer

COVID-19 forced the world into lockdown last year, and that changed the way people work. Handshakes are out, facemasks are in, and many in-person meetings have been replaced by Zoom conferences. Even as some head back into the office, Zoom’s gridwork of postage-stamp-sized avatars of friends and colleagues remains a big part of a lot of people’s workdays.

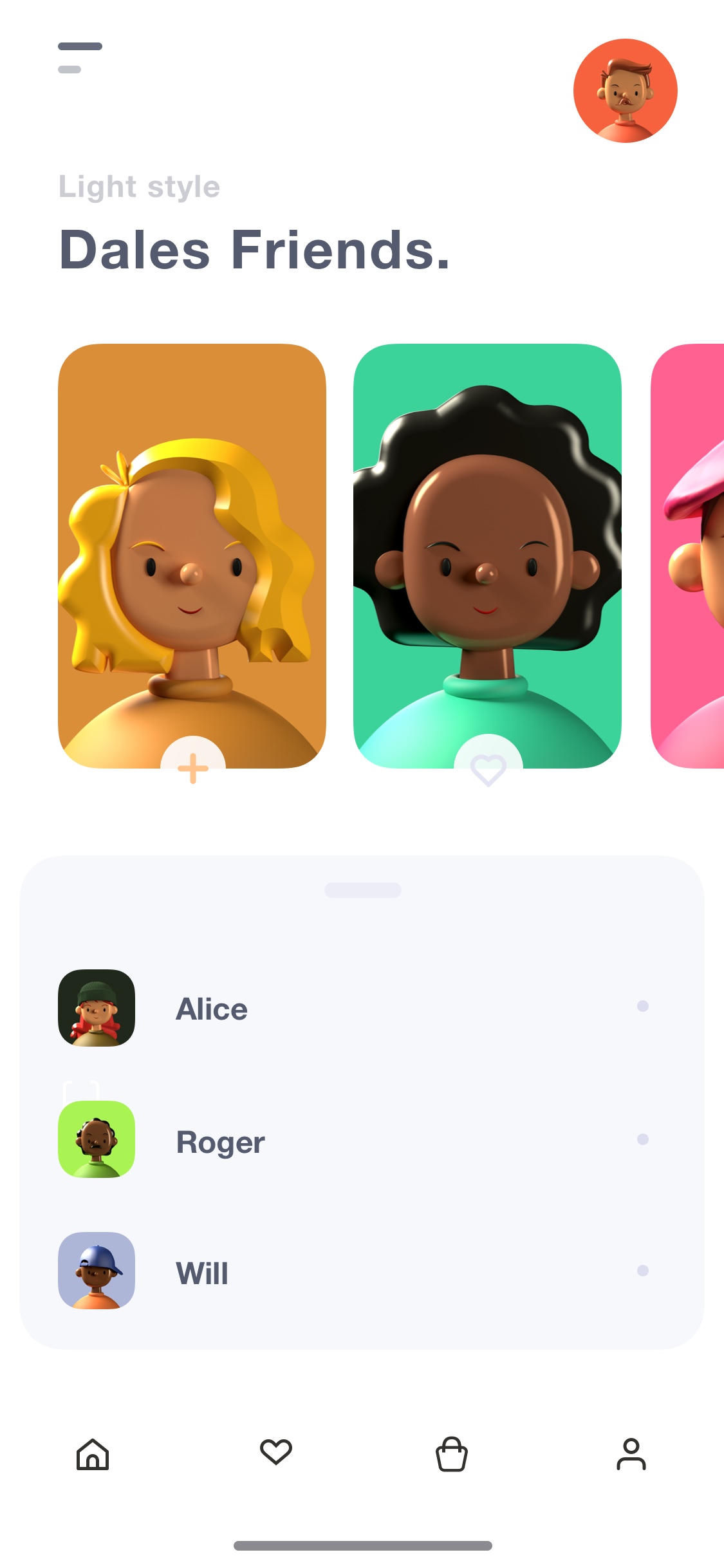

That’s been good news for digital artist Amrit Pal Singh, who spent 2020 experimenting with a new style of portraiture—whimsical toy faces crafted in Cinema 4D and rendered with Redshift. The idea grew out of Singh’s background as a UI designer, and he thought it would be fun to create a set of diverse faces that anyone could use in place of a standard headshot while on conference calls.

Singh launched his Toy Faces project in the summer of 2020, figuring it would be a niche product. Instead, it went viral almost immediately after catching the eye of creative types and others who were suddenly having to attend a lot of virtual meetings. Sensing a business opportunity, he began taking commissions for custom portraits at $100 each. “It was supposed to be a very small subset of the Toy Faces gallery, something like 100 portraits, but that also blew up,” he recalls.

Twitter influencers started placing custom orders and using them as profile pictures, which substantially boosted interest in the project. Singh stopped accepting commissions earlier this year, after creating 2,000 custom Toy Faces. Many for individual users, but he also got orders from a team at Google that needed 100 faces. “With everything moving toward digital, a lot of people need a new profile picture,” Singh says. “But what I really think connected people to the library was that it was a bit nostalgic for them.”

Making Diversity a Priority

From the project’s beginning, Singh knew representation had to be a conscious priority if only to push back against the bias of typical stock illustration collections. “I noticed they all follow a similar style: it would be one South-Asian character or one Black character versus five Caucasian ones,” he says. So he worked to populate the library in a way that gave no particular racial or cultural type a majority, while also bringing his own perspective to the collection.

“I wanted people wearing turbans because I’m a Sikh from India and we wear turbans,” he explains. “Same with the hijab. But I wanted to model it in a fun, different way where it’s seamlessly part of the project.” Doing justice to global diversity is a challenge, and Singh says the process is ongoing. “I keep adding more faces and making it even more diverse, he says. “In the second volume, I included gender-neutral avatars, and I keep talking to people from different communities about how I can represent their people better.”

Singh’s creative process starts with a rough draft in Cinema 4D “I might have a picture in mind that I try to mimic, and most of the time it matches about 70 percent of what I had in mind,” he says. “Abstract illustration might go in any direction, but when I’m creating a Toy Face or a 3D Room, I know what I want, so I’ll just lay out the whole thing with polygons or boxes.”

Though the collection is diverse, it’s also thoroughly templated. The images draw on Singh’s library of interchangeable body parts, hair, and accessories, which makes them look more toy-like, with pieces glued or snapped on rather than growing out organically.

Most of the figures are dressed in turtlenecks, both for simplicity’s sake and as a kind of branding for the series. For lighting, Singh simply mimics standard three-point portrait lighting for photography. “They don’t necessarily work as full-blown 3D objects,” he says. “They are front-facing portraits. That was one reason I was able to do 2,000 faces in six months

Reimagining 3D Rooms

Singh graduated from Vancouver Film School as a motion designer, but when he moved home to India, he found that the motion design scene wasn’t exactly thriving. So he pivoted to product branding and app design for the next eight years, while still flexing his Cinema 4D skills to create assets for his own projects.

With the world in lockdown last year, Singh participated in the annual 36 Days of Type challenge, which got him into the habit of Cinema 4D every day. Being in quarantine also gave him the idea for a creative series about the indoor spaces where we were all suddenly spending so much time.

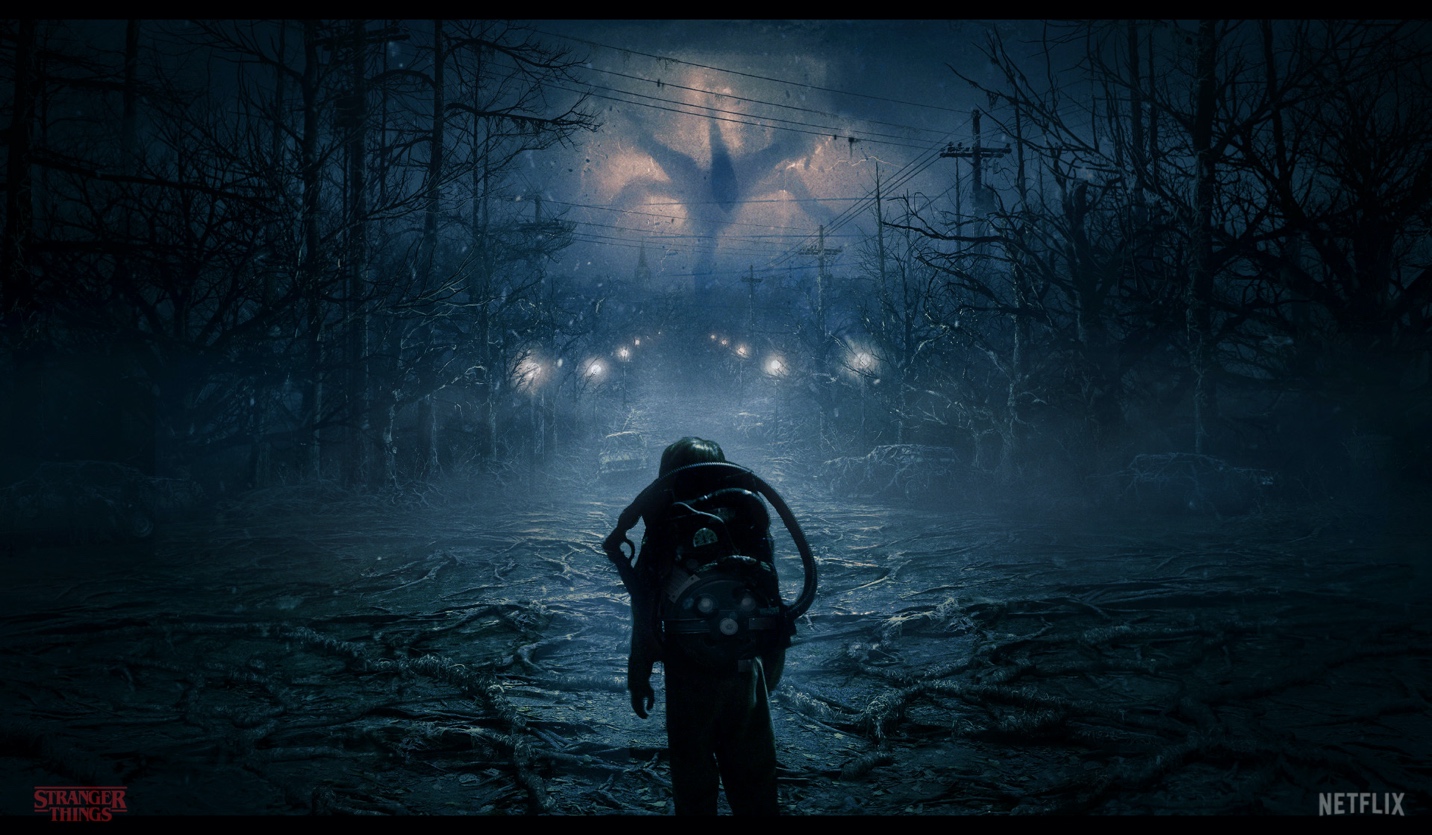

That 3D Rooms Project recreated iconic spaces from literature, film and television from an isometric 3D perspective. After starting with a picture-perfect translation of Vincent Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles, Singh proceeded to create his own miniature versions of rooms from The Jetsons, the Harry Potter series, and Disney’s Aladdin.

Singh made the rooms available as Zoom and desktop backgrounds, but they were also a form of personal expression. “All of these rooms mean something to me,” he says. “I didn’t really care how many people knew The Jetsons. It was a series that I grew up watching, so I really wanted to create a room inspired by it.”

To ensure consistency across the rooms, Singh locked in some design constraints right away. “If I want to do a series, I always make a template to follow, which also helps me have a faster process because all of the rooms have the same structure,” he explains. He likes using Redshift for rendering because he isn’t striving for realism and prefers a stylized approach to lighting, texturing, and everything else.

Rethinking Digital Art

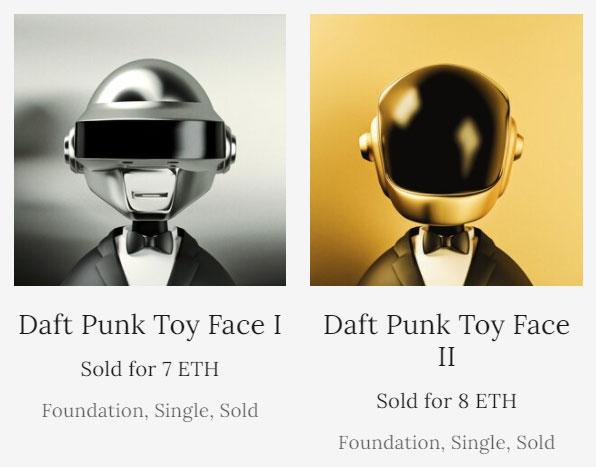

While Singh’s 3D Rooms earned some media attention, it was the Toy Faces project that really resonated with the Internet’s pandemic zeitgeist. Earlier this year, French dance-pop duo Daft Punk abruptly announced their retirement, ad that same day, Singh built two Daft Punk toy faces and auctioned them off as NFTs—unique editions of digital artwork authenticated and tracked using blockchain technology. The duo sold for a total of 15 ETH, the equivalent at the time of around $25,000.

Enthusiasm for NFTs has waned a bit since reaching eye-popping heights a few months back, but Singh is among those who believe the NFT marketplace is here to stay. “It’s an absolute game-changer for 3D artists,” he says. “This is the way for digital artists to catalog their work and save their legacy online, and these technologies are the building blocks for people to create a digital museum. We have to see it in that light.”

To that end, Singh just opened the Toy Face Café, an art gallery in Cryptovoxels, a virtual world backed by the Ethereum blockchain. The digital space features Singh’s own Toy Face NFTs along with highlighted work by other digital artists. He says that when he started releasing NFTs, they changed the way he looked at his own work as an artist, making him more consciously expressive while still working within the framework of the Toy Face series.

Active on Instagram and Twitter, Singh markets his own work, and also acts as an advocate for the digital art community. Though he didn’t use to think it was important for 3D artists to have their own style, he now believes that having a strong individual style is important because it helps give artists a recognizable brand. “Having a particular style helps me market my work in a much better light,” he says. “Once you see my portfolio, you’re not expecting me to make a realistic model for you. That works better for me, and it works better for you.”

Bryant Frazer is a writer in Colorado.