Saad Moosajee and his team on creating the music video for Joji’s “777”.

By Meleah Maynard

New York City-based director Saad Moosajee has always found Renaissance art interesting because “it evokes God and has a holy quality, even when it is shrouded in darkness,” he explains. Even so, it’s an aesthetic he hadn’t worked in much until recently, when Japanese singer-songwriter, Joji, contacted him about directing a music video for “777,” a track from the artist’s latest album, Nectar.

Already known for his visually compelling work for Thom Yorke and Mitski, Moosajee was intrigued by the idea of directing something completely different. So, knowing that the number 777 is considered to be spiritual, and the opposite of 666, he pitched the idea of making a video with the look of a living Renaissance painting.

Joji gave the green light and Moosajee assembled team, which he led with production company Pomp&Clout and VFX supervisor James Bartolozzi. Made under COVID-19 restrictions, the video combines Cinema 4D, Unreal Engine, Marvelous Designer, ZBrush, and Houdini work by Swordfish San Francisco. And though it looks like there is an entire troupe of dancers, there is really only one, Maya Man, who becomes the entire cast thanks to experimental motion capture techniques by Silver Spoon and the animation team.

We talked with Moosajee, as well as designers/animators Zuheng Yin and Chanyu Chen, about the making of “777,” which was first featured in October as an exclusive release for the launch of Apple’s free, 24-hour music video live stream channel, Apple Music TV.

Tell us about how you approached this as a moving Renaissance painting.

Moosajee: The idea was not just to recreate Renaissance paintings, but to make something that evoked that aesthetic in motion. One of the main things I focused on was lighting. I tend to think through art direction and lighting. I came up with a technique to have tons of individual lights with a very specific angle, so you get a contrast effect called Chiaroscuro. Through that contrast, I was trying to combine the feel of fleshy human skin with intense dramatic lighting to get that Godly Renaissance feel.

Chen: We wanted scenes that depicted multiple tableaus’ movements interacting with our main character. Since there are multiple layers of complexity in Renaissance painting, we carefully and precisely considered the characters and their costumes in each shot.

Moosajee: We started with still frames and made static images that felt like religious paintings. From there, we thought about how to bring things to life. I usually do a combination of character animation and motion capture but, for this, I thought motion capture would be best, so we contacted a studio called Silver Spoon. Next, I found the performer, Maya Man. She is a dancer and choreographer and had never done anything like this before. Dance felt like the most natural way to create a living figurative painting because it is so expressive and there is so much intricate detail in the way dancers move.

Describe how you created many different performers using only one dancer.

Moosajee: These types of paintings usually have so many characters. It was pre-photography, so painters were obsessed with creating three-dimensional forms. They wanted to show the human body from all angles and all forms of beauty. I thought it was really cool that with a 3D figure, we could do what they were imagining and then flatten back to a painting, as well.

Yin: We also made some of the movement intentionally offbeat to add more realism to the piece. It was amazing to see several people communicating and gesturing to each other, knowing they were really all the same person.

Moosajee: Because of COVID restrictions in New York, where things were pretty bad at the time, we couldn’t get a bunch of people into one room and be safe. So we had just a few of us working together, socially distanced and wearing masks. Maya and I had to rehearse remotely and we would use Unreal Engine to do real-time playback for the choreography of each character during the motion capture shoot.

It was like 3D onion skinning with people instead of cel animation, but it made it so she could do a take, see it in real-time and perform against the next take as if it was a different person. We did that for all of the people in the video, which gave the impression that there were many different performers. The whole thing was so insane, and Maya had never done motion capture dance before. But she is an incredibly good dancer and she adapted on the fly and figured it out.

Chen: I got the choreographed motion capture data from Unreal and brought it into Maya where I retargeted the data onto the various characters. Then, I exported either a baked alembics or FBX for finishing. Eventually, we created a library of CG performers that could be used in either Cinema 4D or Houdini. Our job as animators was to compose the scenes of characters so they felt like theatrical groups of dancers interacting with one another.

Walk us through your process for this.

Moosajee: My specialty is on the design and lighting side of things, so I often designed and lit scenes while Chanyu and Zuheng animated and assembled them. Camera work, lighting, framing and blocking are all done in Cinema 4D to set the visual tone and art direction. That process of visual direction is a common thread though all of my projects. We emphasized a collaborative workflow so other members of the team who specialize in Houdini, Marvelous, ZBrush and other tools could funnel into the pipeline.

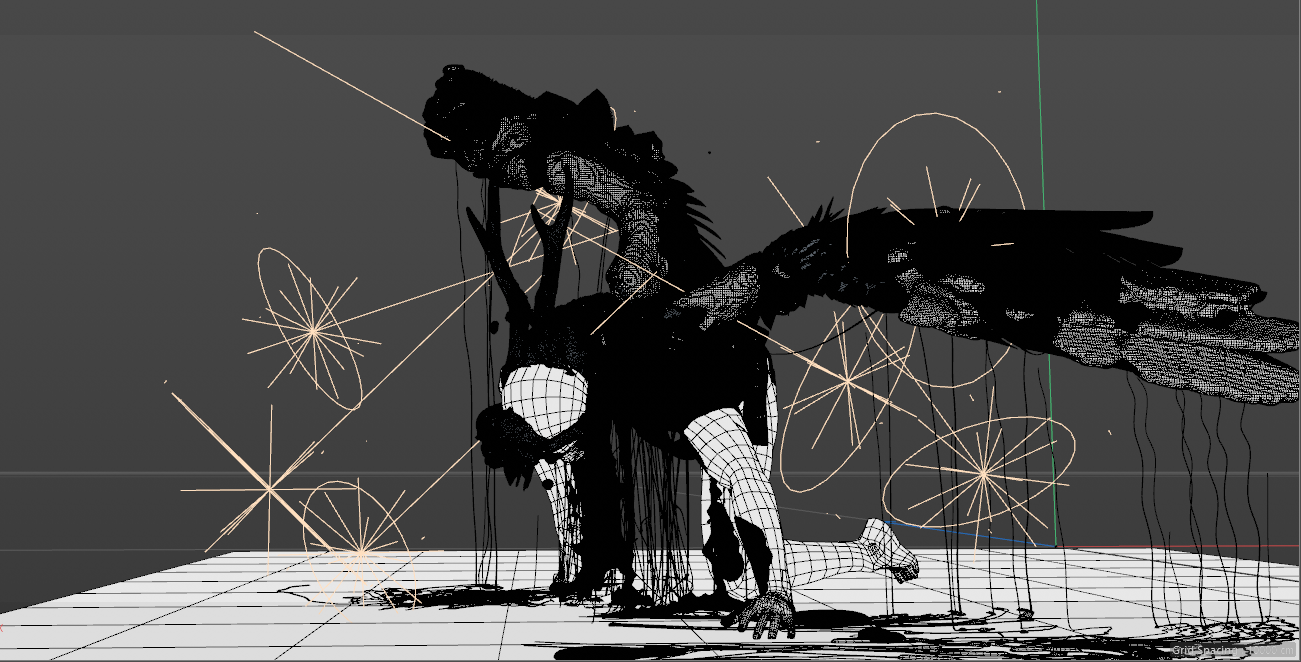

Yin: I really wanted the angel wings scene (above) to feel iconic. After we got the motion capture data for the moment the scene begins, I started the shot by pairing the wings onto the figure. The wing is usually considered a sacred narrative symbol, and the painful animation where the wings burst from the character’s back caught my eye.

I wanted it to catch the audiences’ eyes too, so I animated many of the feathers manually to give the scene an angelic feeling. Once I animated the wings, we simulated it again in Houdini to add more realism to the individual feathers, as if they were blowing in the wind.

Moosajee: We used C4D for all of the lighting, and one thing that emerged for us was that it became so real once we animated various lights. That added another element of realism. It ended up feeling like a play or an opera. The opening table scene (below) is a key moment in the film. It references both Renaissance still lifes and the stage of an opera, establishing a theatrical setting for the piece.

Cinema 4D was our core application, and we used Maya for basic rigging. I use C4D for all of my projects, and I bring everything into it because I think it’s the most streamlined tool for lighting and animation. We processed the motion capture data in Maya, and we spent a lot of time getting the movement of the angel wings right.

We also had someone really finessing the simulations in Houdini. Some of the cloud scenes were so intensive they had to stay in Houdini, and we rendered them entirely that way. Marvelous Designer and ZBrush were used for the props, clothing and skulls. It was the most applications I’ve ever used on a project.

What kind of feedback have you gotten so far?

Moosajee: I never thought people would think this was live action, but a lot of people have asked about that. It’s all CG, though I know some parts feel more painted than others. I like the way it ebbs back and forth between the worlds of dance and a more painterly look. It was really interesting to try something different with this one.

Meleah Maynard is a writer and editor in Minnesota.