Chicago-based Sarofsky on using C4D, Houdini and more for the FITC Toronto 2020 titles.

By Helena Corvin-Swahn

FITC Toronto 2020 was canceled due to the coronavirus, but the main titles for the event premiered on April 19 during a live Mograph.com podcast with Chicago-based production house, Sarofsky.

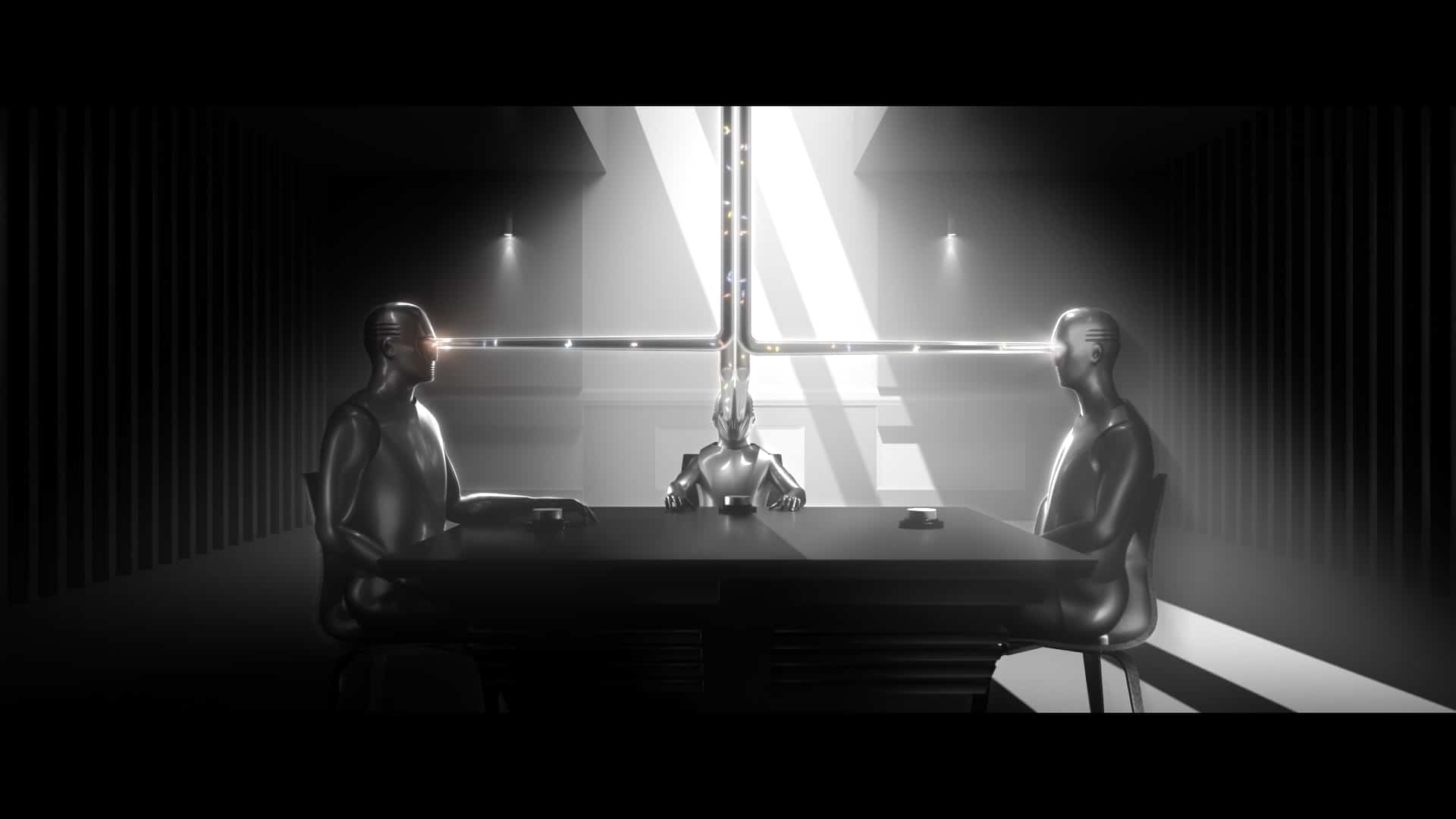

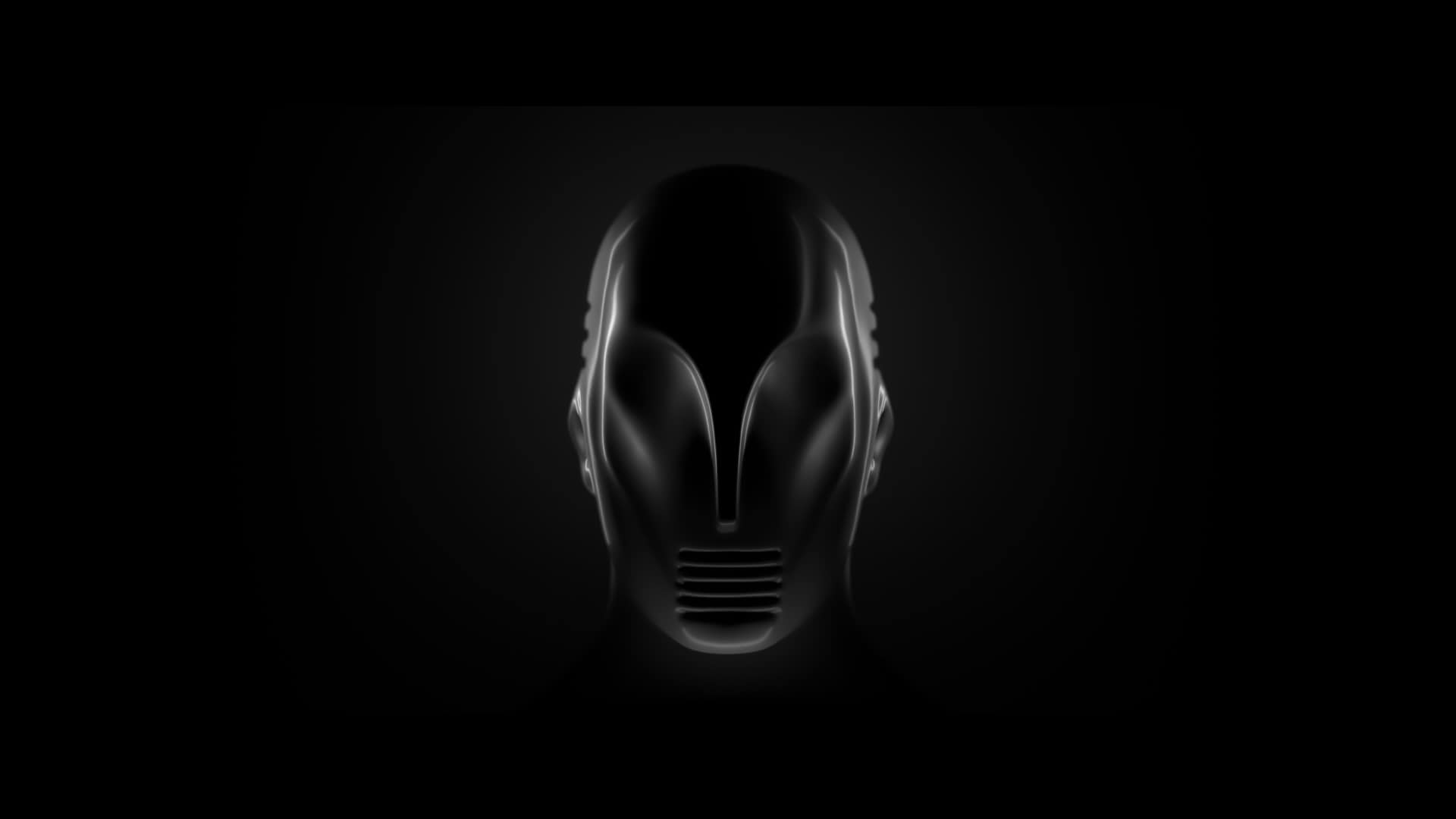

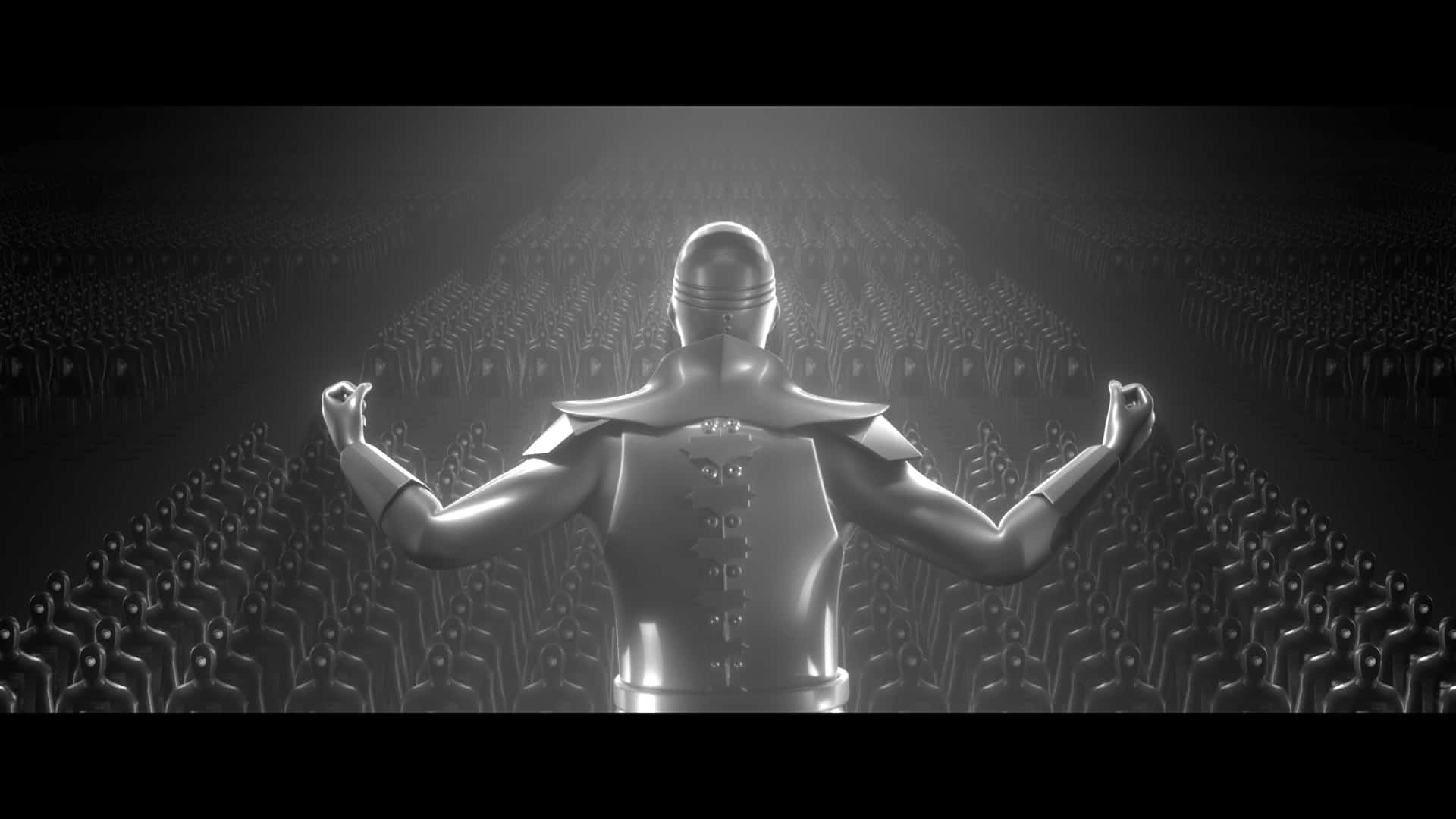

Aptly named, What You May Find, the FITC titles offer a dark and referential vision of a future in which technology and innovation are used to manipulate and homogenize humanity. Erin Sarofsky, who founded her design-driven production company in 2009, says her team was honored when FITC founder, Shawn Pucknell, asked them to create the titles. And, using a combination of Cinema 4D, After Effects, Houdini, X-Particles and Arnold, they sought to “create something extraordinary.”

Here Sarofsky, along with production house’s co-director, Duarte Elvas, and lead artist, Jake Allen, talk about their process for creating the titles.

Erin, what was it like to collaborate with FITC?

Sarofsky: Shawn and the FITC team were wonderful. It was a milestone year for the event, and we really wanted to make sure our work lived up to expectations. We loved that they respected our creative freedom. And they were super engaged in the process, contributing with audience insight, guiding the initial brainstorming session, and setting up regular check-ins and a formal schedule, which was really helpful to keep us on track.

Describe the brief and how you approached it.

Sarofsky: Shawn wanted the titles to be themed around the future and we wanted a concept that aligned with FITC’s core attributes—Future, Innovation, Technology and Creativity. We started the process by brainstorming what we thought the year 2020 would look like when we were kids. For me, it was rooted in The Jetsons: flying cars, robot housekeepers and jet packs. Of course, someone also mentioned hoverboards. Eventually, we talked about the “alt” future, and that was a real pivot in the conversation because we all realized that while technology can delight us, innovation and technology can also be used to manipulate and homogenize us.

Sarofsky: It was that moment that we realized we wanted to make a piece rooted in futurism that warned, or speculated, that technology could be used to really manipulate humanity into a totalitarian structure. That isn’t just a national issue, it is a global issue. And humans need to start seeing the beauty in our natural differences because total homogenization is way scarier than individuality.

Why did you choose to use the 1969 track, “In the Year 2525”?

Sarofsky: Someone remembered the song, which is by Zager and Evans. We loved the old, folksy sound; the dark, strange lyrics; and that the way they described things was open to interpretation.

Duarte Elvas: Listening to the dystopian lyrics made visuals start popping into our heads immediately. We were also very drawn to the way a lot of the verses related to events, as well as the scientific/technological advancements we are seeing today. It seemed like a great base from which to tell a visually rich and compelling story that comments on where we could be headed. That’s how we came up with What You May Find.

Talk about your inspiration and concepting for this.

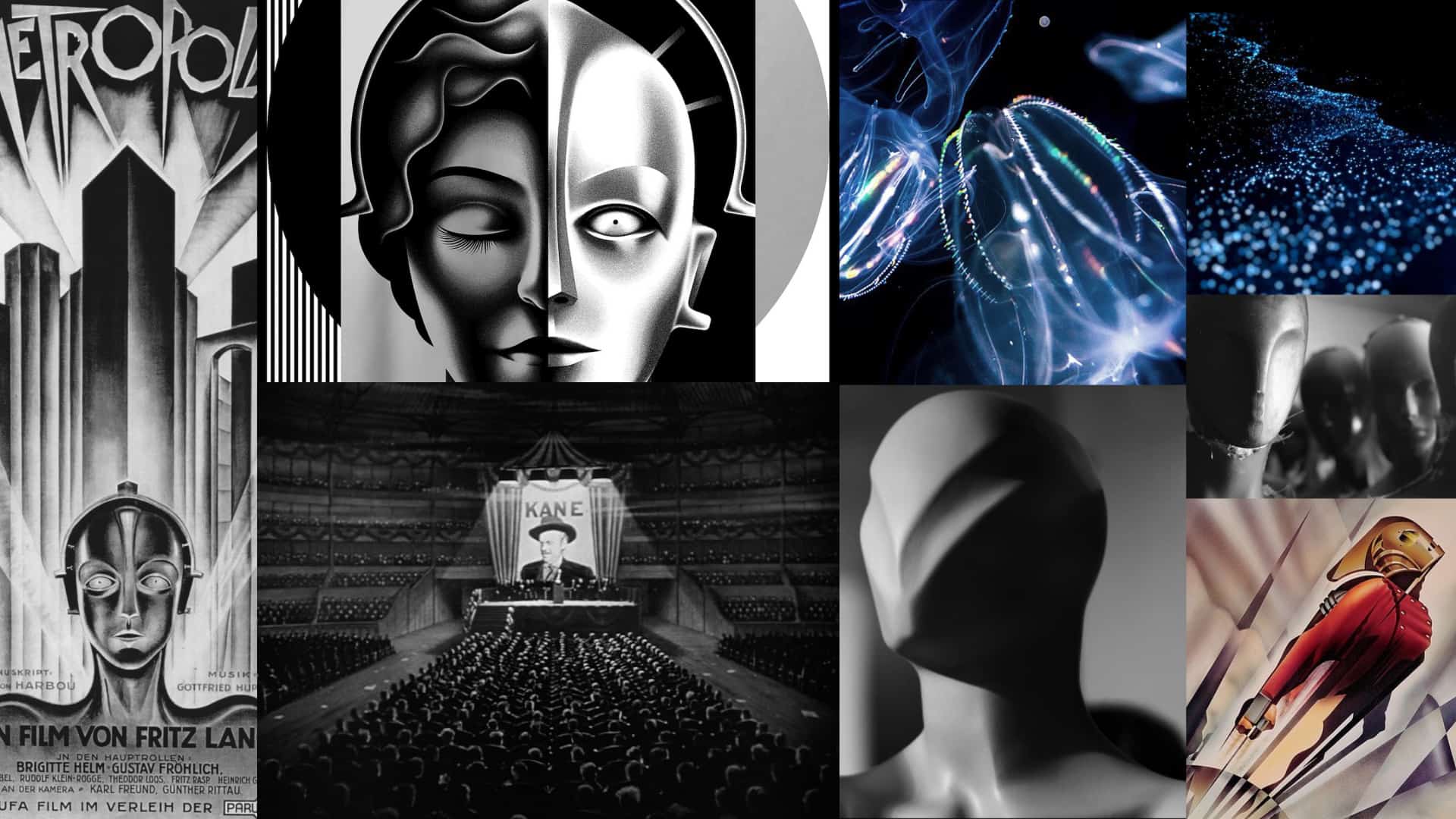

Sarofsky: We referenced the films Metropolis, 1984 and Citizen Kane, as well as a bunch of art deco illustrations and architecture.

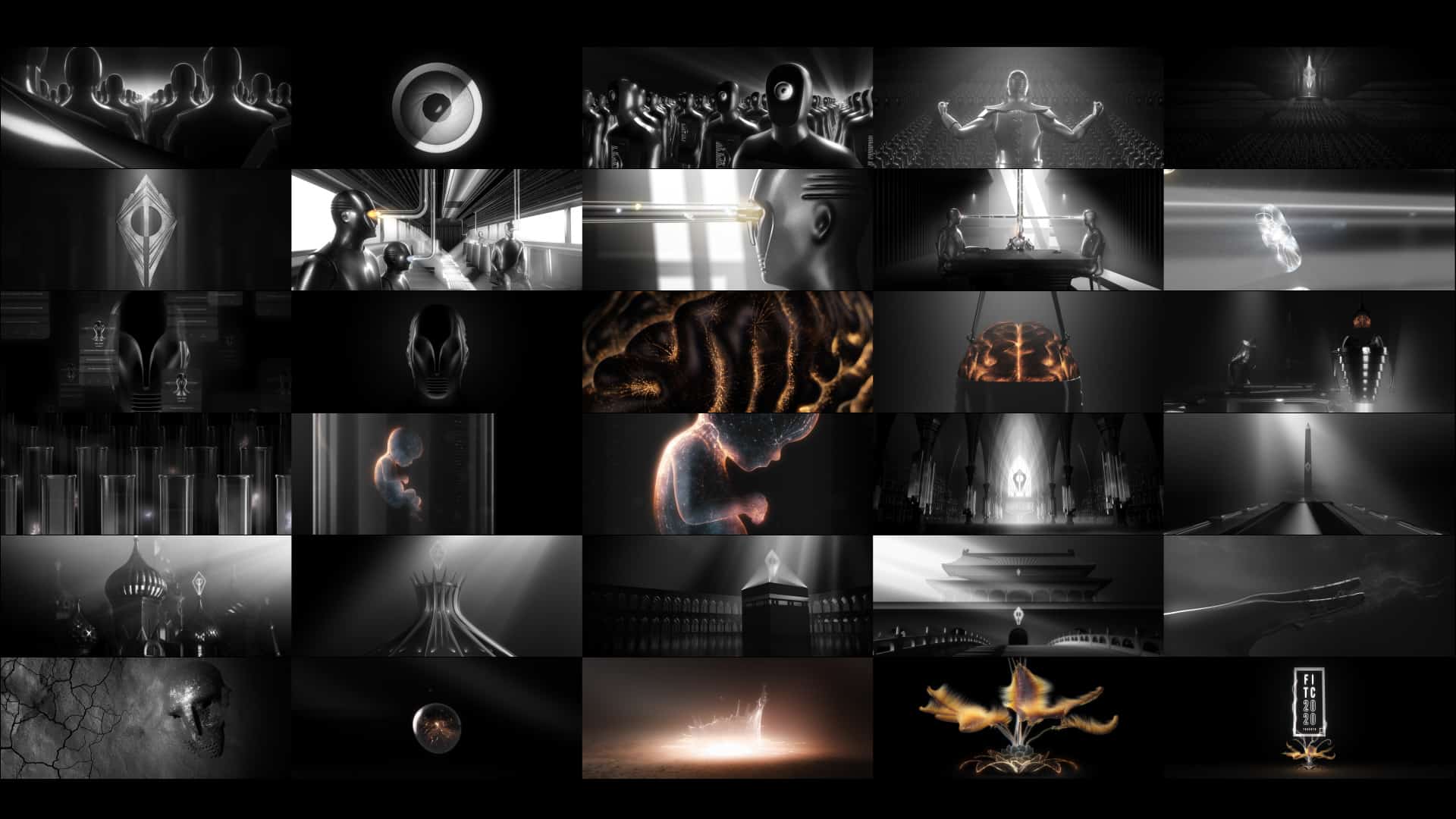

Elvas: As with all our projects, we worked hard on the nuances of the concept which, while informed by the lyrics of the song, involved coming up with scenarios that illustrated our vision of the future. We broke the script/lyrics into verses and imagined a scenario for each verse based on the images we envisioned. Then, we created a storyboard for each of those scenarios to get a rough idea of the content and composition of each shot. Once we cut the sketches to the song, we had an animatic, which was a strong base for artists to start creating assets in 3D.

What did you find most challenging about this project?

Sarofsky: Our biggest challenge was how to develop a consistent look that felt both photo real and heavily stylized, almost illustrated. The key was mixing strong design elements into various scenes, like rays of light. So, some of the lighting is natural to the scene, and some is heavily manipulated based on the overall design aesthetic. In general, we made sure all the compositions are super design driven, while still being focused on telling the story. We also used a very limited color palette, mostly black and white, but we occasionally pulled in metallic tones, like copper, gold and gun metal.

Describe some of the technical aspects of the project?

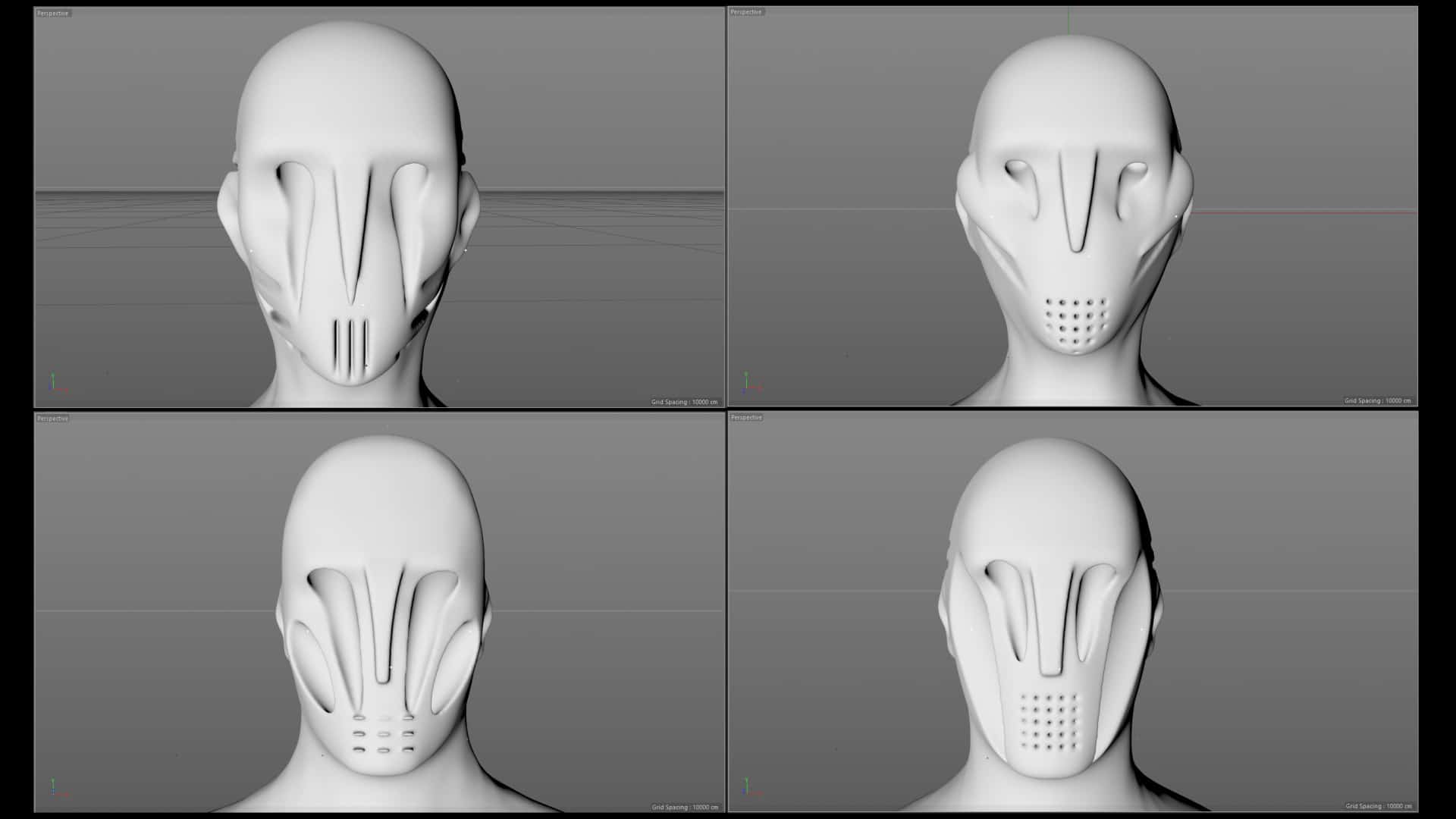

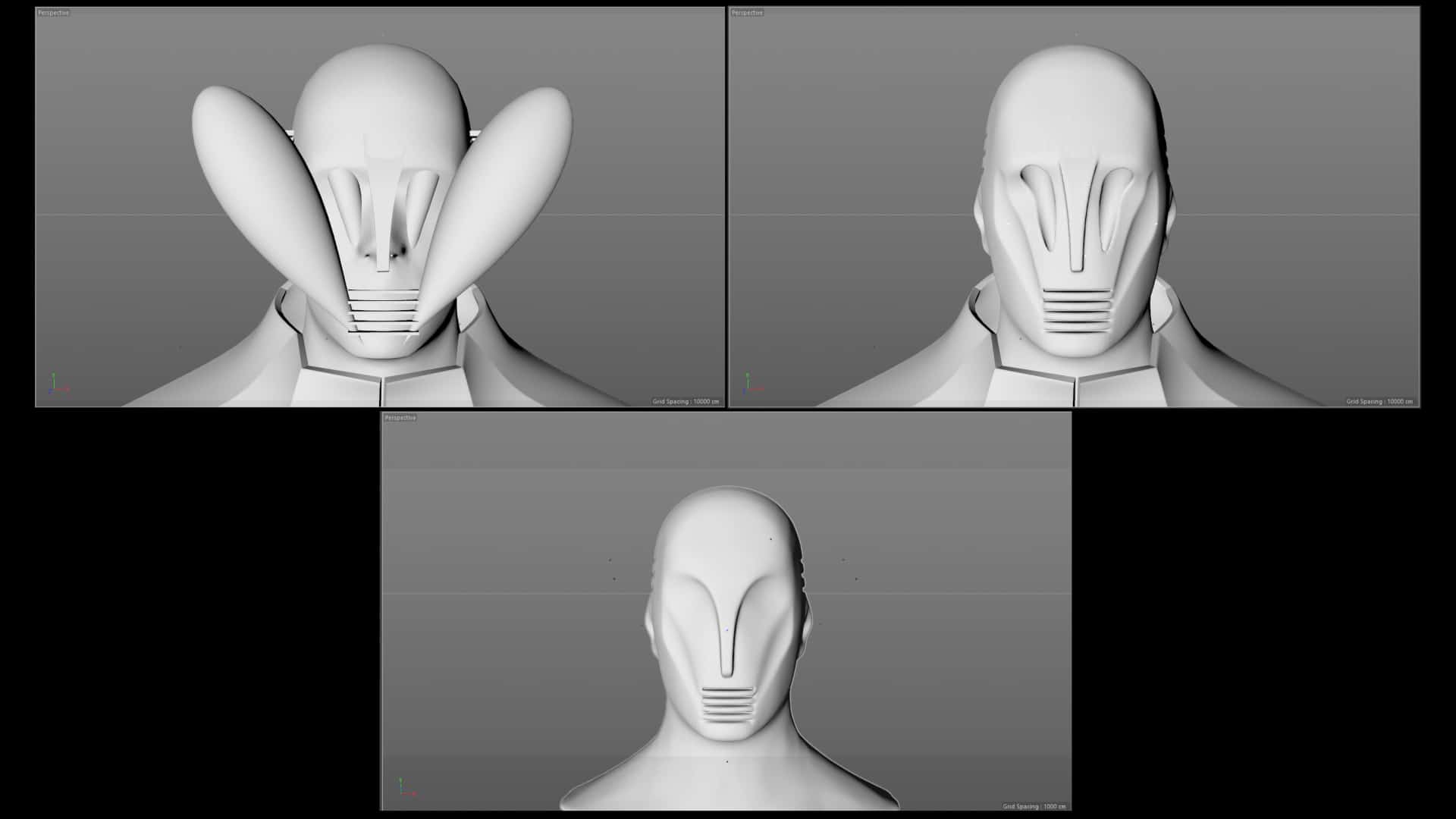

Jake Allen: We started by using our sketches to model our assets in Cinema 4D. Some of the assets in our shots didn’t require animation, so we ended up taking advantage of Cinema 4D’s Volume Builder toolset to model the shapes subtractively, while keeping it all procedural for when changes needed to be made. That strategy was invaluable when creating things like the characters’ faces, their armor and the world government logo. Anytime we needed better topology, we used the Quad Remesher plugin for Cinema 4D.

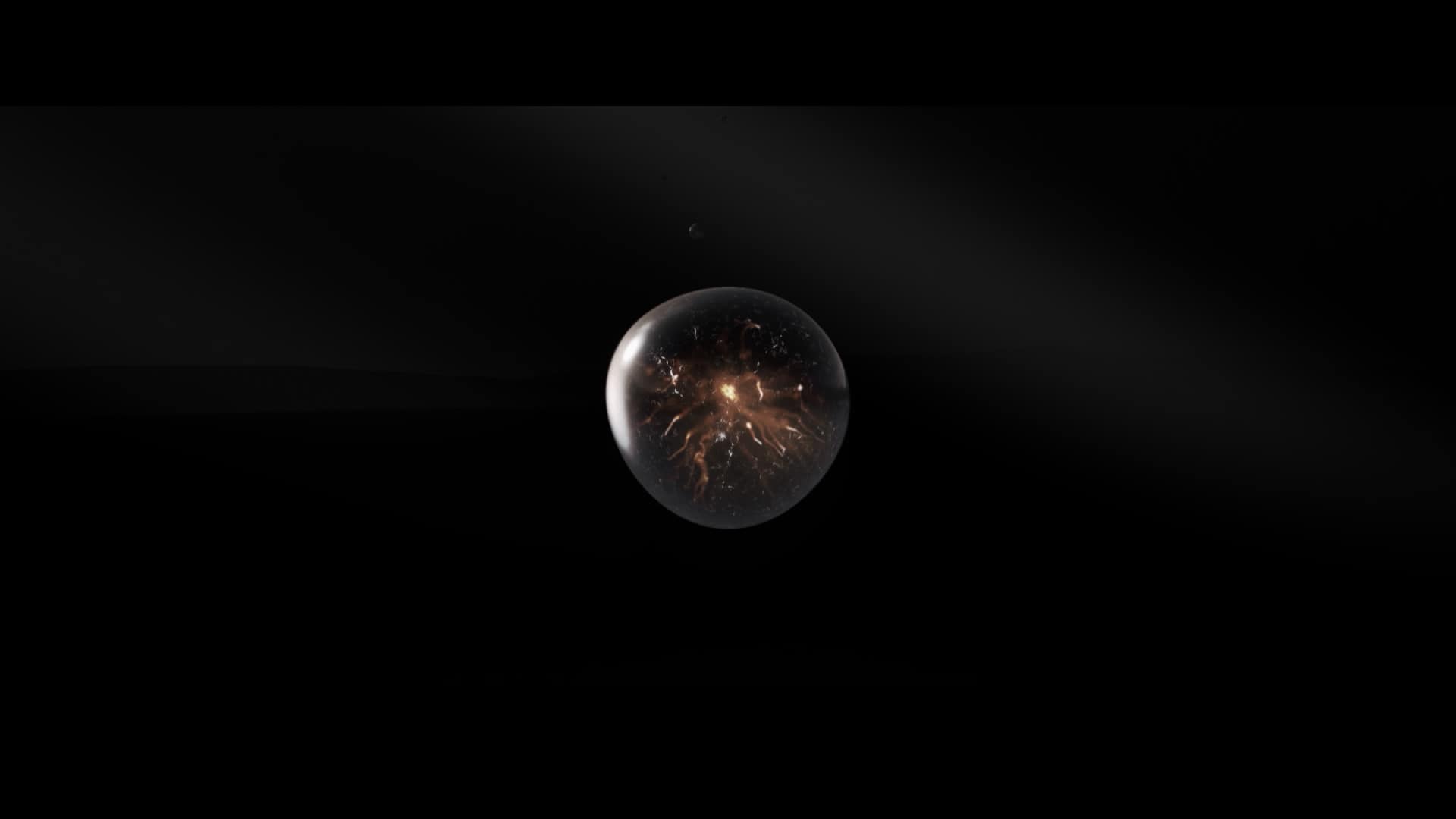

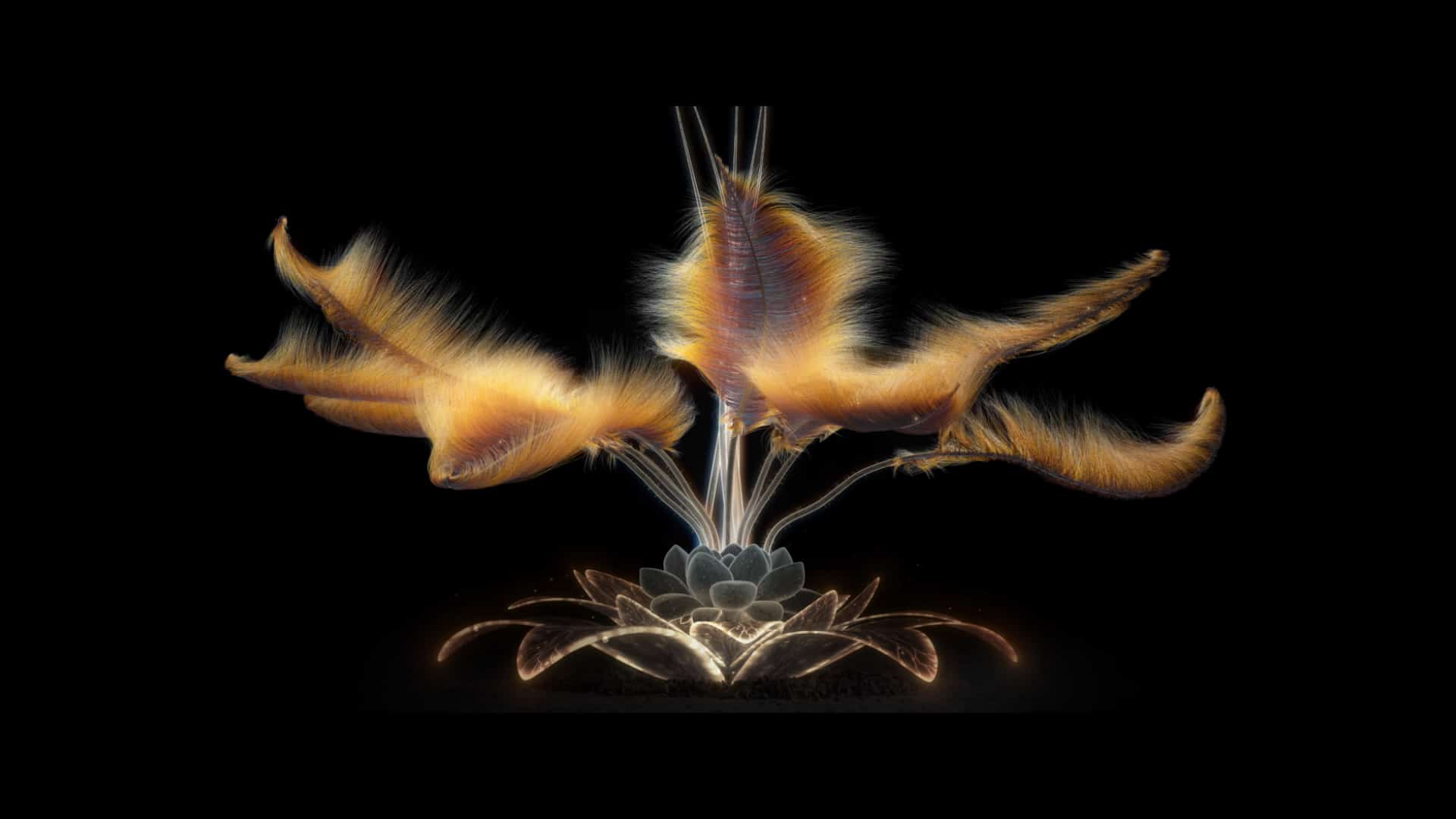

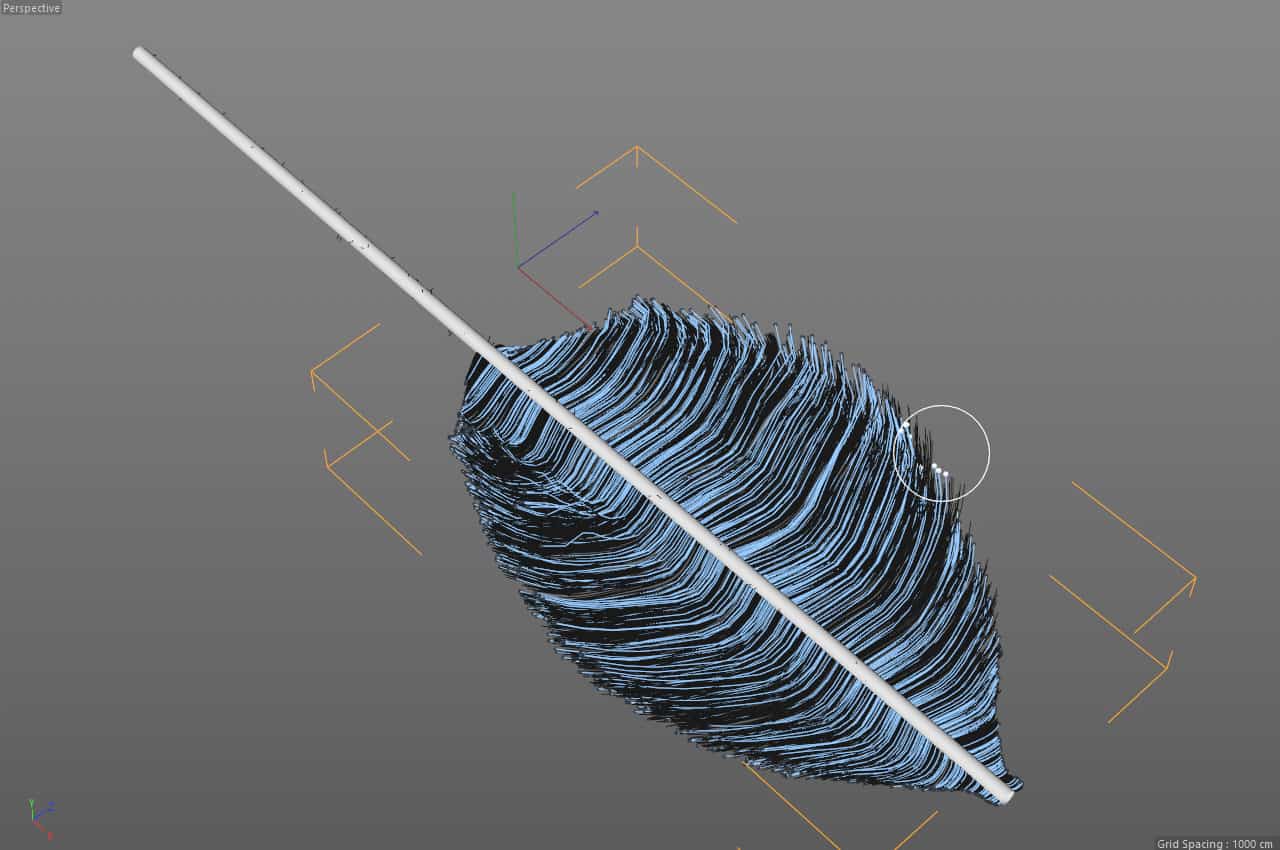

Sarofsky: The flower at the end of the sequence is all about expressing hope and the rebirth of the planet. So we designed it to look alien. To accomplish that, we discussed how lovely it would be to have the flower unfurl feather-like tendrils rather than petals. Jake took that challenge straight into Cinema 4D.

Allen: We were familiar with C4D’s Hair system, so we decided to experiment with feather effects using that. For the basic setup, we created a tube with hair on either side that we shaped into a feather, using the brush cutting tools. We used various ramps and gradient maps to control both the color and the length of the plumes. By animating those gradients, we were able to have the feather appear to grow over time. We cached that, and the simulation engine came up with the dynamics for us.

We enabled the hair, controlling the length with a gradient. When we combined everything together, leaving dynamics on and gravity off, along with a little bit of turbulence, we got something that looked really interesting with an underwater feel. After it was cached, Cinema 4D’s Hair material applied kinks, curl, and noise, turning it into something we felt was very cool. From there, we worked out how to duplicate each stem and feather system, and then we cached each one. When animated, the motion of the feathering looked organic and natural.

Tell me a bit about the tools you used for shading and lighting?

Allen: Shading and lighting were done in Arnold for Cinema 4D, and we relied heavily on light linking in order to have per-object or per-character light setups that could be cloned and duplicated. When we could, we used gradients and noises in textures to art direct highlights, rather than using physical lights themselves. This kept renders lighter, but also meant that specifically placed highlights wouldn’t disappear when the camera moved. Everything was composited in After Effects where we added color correction and extra elements to scenes, such as volume lights, particles and glows. We split up the shots into separate renders and used XRefs to keep scenes from getting too heavy, and to keep things flexible if changes came down the line.

What challenges did the dynamic elements present?

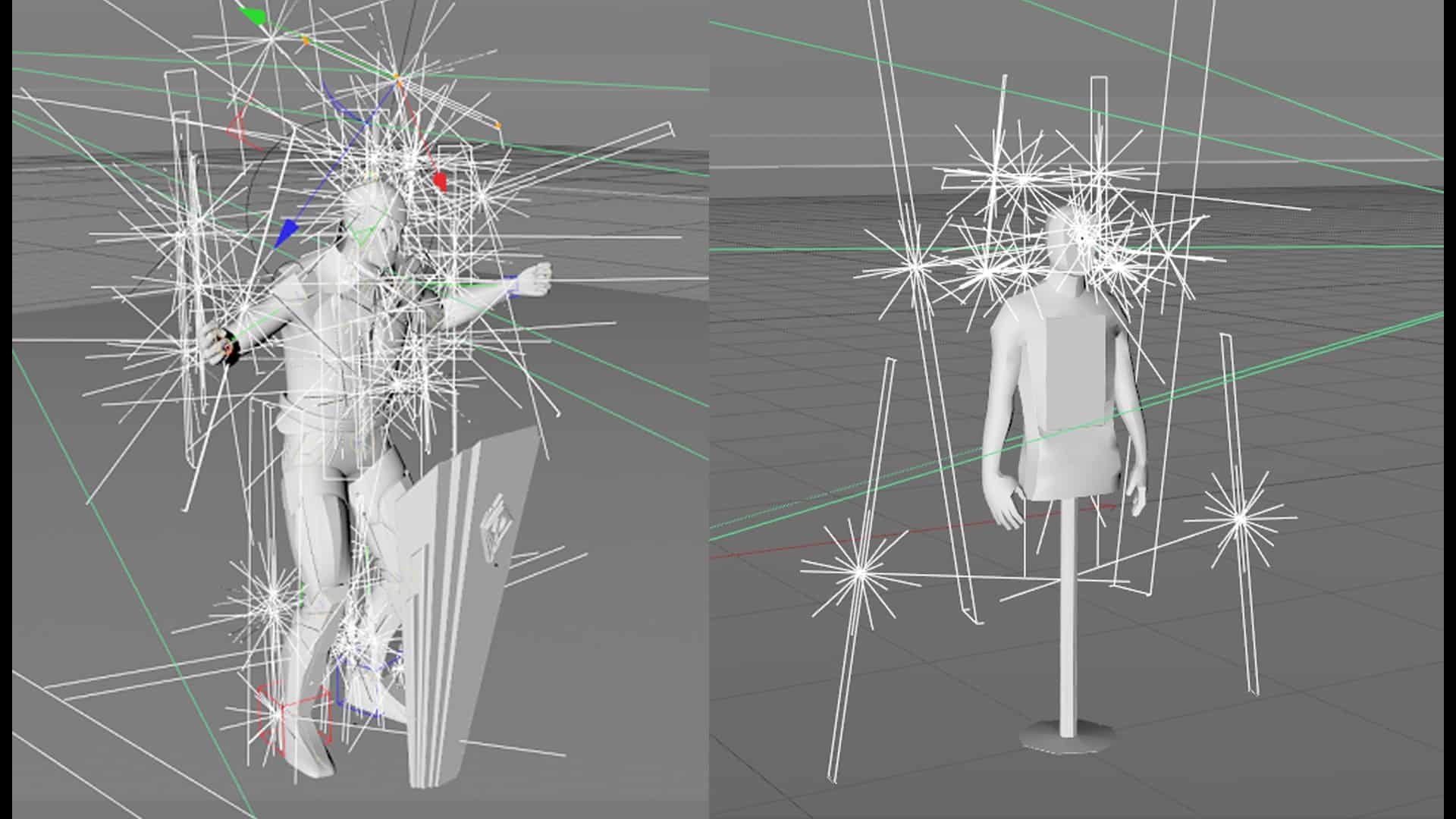

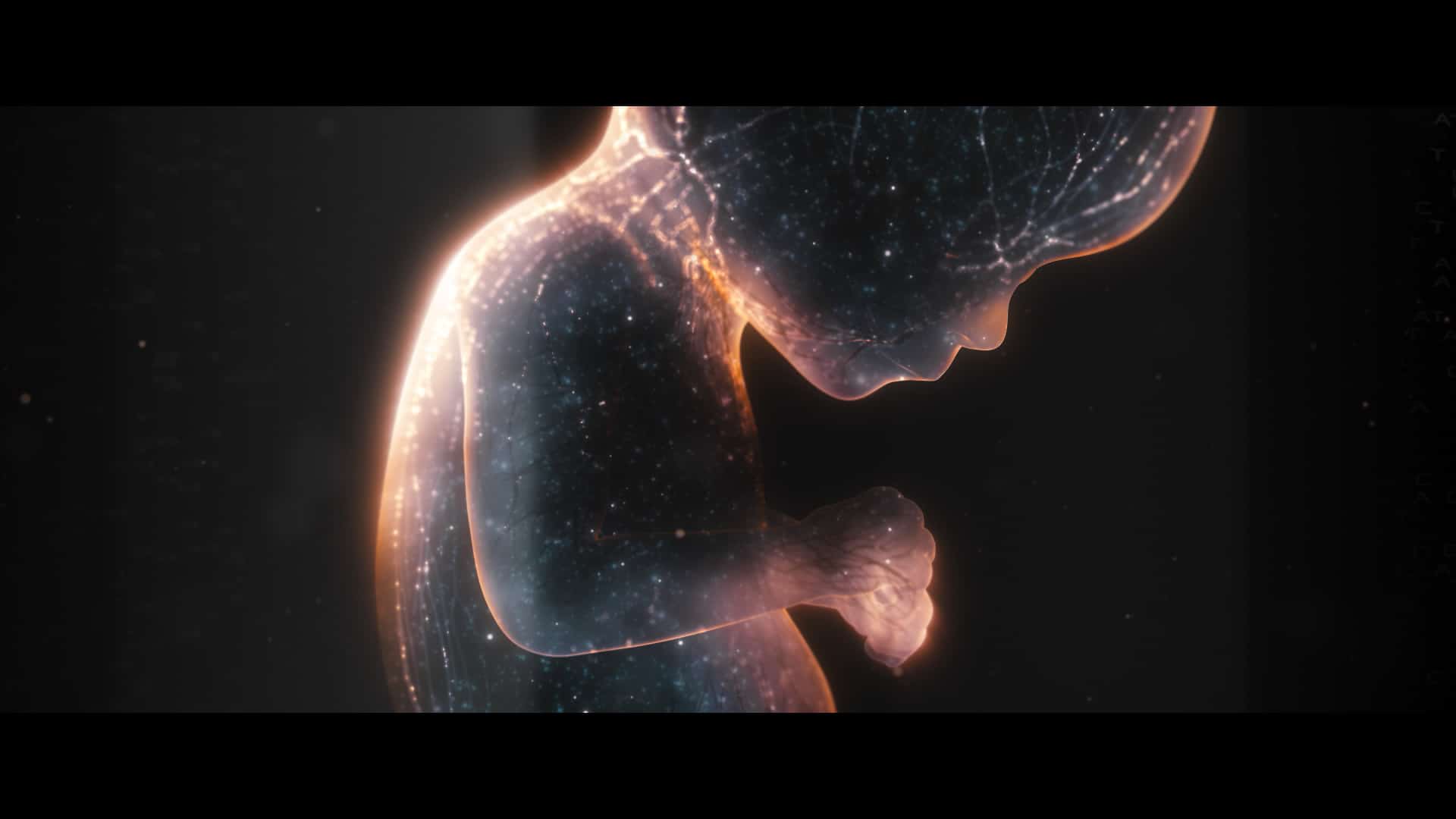

The biggest challenges were particles, dust, and smoke. We were able to leverage X-Particles in a lot of scenes, like the one where you see a disintegrating hand. And we used baked Ambient Occlusion textures to generate particles in the crevices of the brain. The vein networks on the brain, and the scene with the baby were also challenging. A particle-based solution would have worked, but we needed to control where the points would start and end, so we used a setup in Houdini that created vein networks without the need to run a simulation. The models were imported as alembic files, and the Find Shortest Path node generated curves we could export as alembics back into Cinema 4D.

What message did you want people to take away from this?

Sarofsky: While it is quite a dark piece, we do see it as ultimately an expression of hope. I love when the colored flower breaks through at the end. It shows that despite this being a somber visual exploration of a dystopian future, there is still hope that nature and individuality will persevere.

Elvas: I really love that this is a thought-provoking piece that can potentially raise awareness to what is right and wrong with the world today. The more controversial aspects of the piece may have the potential to change the way people look at the world, and hopefully influence their choices and behavior. Looking into the future and seeing how scary the world can become, but ending on a positive and hopeful note, was my favorite part of this whole process.

Watch the Mograph Podcast interview with Sarofsky below

Credits:

Special Thanks to the FITC team led by Shawn Pucknell

Design/Production Company: Sarofsky

Director: Erin Sarofsky

Co-Director: Duarte Elvas

Executive Producer: Steven Anderson

Producer: Kelsey Hynes

Lead Artists: Josh Smiertka, Jake Allen, Tanner Wickware,

Matt Miltonberger

Additional Design and Animation: Ally Munro, Griffin Thompson, Andrew Hyden, Dan Moore, Tobi Mattner, Nik Braatz

Additional Contributors: Jamie Gray, Andrew Rosenstein, Mark Galazka, Kenny Albanese

Music Supervision: Groove Guild

Final Mix and Sound Design: Groove Guild

Music Track: “In the Year 2525”

Composer: Richard Evans

Performed by: Jon Notar featuring Jean Rohe

Master Recording: Groove Guild

Publisher: Zerlad Music Enterprises, Ltd. (BMI)

Worldwide Rights Administrator: Grow Your Own Music (BMI), a division of “A” Side Music, LLC d/b/a Modern Works Music Publishing

Helena Corvin-Swahn is a writer in the UK.